Double Taxation and invoking the Mutual Agreement Procedure

What is the Mutual Agreement Procedure?

As our economy globalizes, it is common today for individuals and families residing around the world to be subject to taxation on their income in more than one jurisdiction. As a result, the risk of double taxation is a genuine consideration for many global families. Tax Treaties between countries provide a means of resolving the potential for double taxation by the allocating taxing rights between countries based on agreed principles. However, not all issues are addressed in the Treaties.

In cases where the Treaty is not clear on which country has primary taxing rights, a resident of a jurisdiction to which the Treaty applies can invoke the Mutual Agreement Procedure (MAP). The MAP is essentially a negotiation process between the relevant tax authorities (“Competent Authority”) to resolve double taxation issues and Treaty related issues.

When can you invoke it?

In the US-Australia cross-border context, the MAP could potentially be invoked where there is uncertainty as to the application of the Tax Treaties and allocation of taxing rights in the following contexts:

Example 1: Foreign tax credits

In an M&A context, if the US anti-inversion rules apply in a cross-border restructure – for example in a “scrip for scrip” exchange which results in a US entity’s business activities being placed under the control of a foreign entity – an Australian holding company could be subject to US Federal corporate tax and withholding tax (on dividends paid to its shareholders), and filing and reporting requirements.

This then raises the following considerations:

- The US imposes a 30% withholding tax (unless reduced by a treaty) on dividends paid to foreign investors for US sourced income that is not effectively connected with the conduct of a US trade or business (IRC section 881). Dividends are generally considered US sourced income if paid by a US domestic corporation (IRC section 861).

- Consequently, the effect of the anti-inversion rules could be that dividends paid by the Australian holding company are characterized as US sourced income and subject to the 30% withholding tax in the US.

- Australia would impose corporate tax at 30% on the taxable income of the Australian holding company (and grant a franking credit to its shareholders on the franked dividends paid).

- It is unclear whether foreign tax credits would be available in Australia in respect of US federal corporate taxes and withholding tax payments triggered by the anti-inversion rules – this would depend on how the US-Australia Tax Treaty is applied. If the Treaty is interpreted unfavorably, this would result in the double taxation of both corporate profits and dividends.

Article 1(1) of the US-Australia Tax Treaty states that the treaty’s benefits “shall apply to persons who are residents of one or both of the Contracting States” (i.e. the US and Australia). A corporation that is treated as a corporation for US tax purposes is specifically excluded from the definition of US resident (Article 4(1)(b)(iii) and Article 2(g)(i)). However, the definition of Australian resident includes an Australian corporation (Article 4(1)(a)(i)).

The Treaty states at Article 22:

“(2) Subject to paragraph (4), United States tax paid under the law of the United States and in accordance with this Convention… in respect of income derived from sources in the United States by a person who, under Australian law relating to Australian tax, is a resident of Australia shall be allowed as a credit against Australian tax payable in respect of the income. The credit shall not exceed the amount of Australian tax payable on the income or any class thereof or on income from sources outside Australia. Subject to these general principles, the credit shall be in accordance with the provisions and subject to the limitations of the law of Australia as that law may be in force from time to time.”

It is unclear whether the Treaty relief that is available “in respect of income derived from sources in the United States” would be available in respect of taxes paid as a result of the application of anti-avoidance rules. The Australian Holding Company would need to invoke the MAP by submitting its case to the ATO.

Example 2: The taxation of foreign beneficiaries of Australian resident non-fixed trusts on capital gains which do not have an Australian source

This is a situation that can arise following the release of the ATO’s draft Taxation Determinations TD 2019/D6 and TD 2019/D7, discussed in our blog and Structuring cross-border transactions: part 1 white paper on this topic.

Generally, where income has the potential to be taxed both in Australia and in the US, treaty relief may be provided by the country of residence crediting the tax paid or payable in the source country against the tax payable in the country of residence (Article 22 of the US-Australia Tax Treaty). How do the taxing rights apply if Australia is technically not the “source country” of the capital gain and the only connection to Australia is via the Australian residency, and (non-fixed) form of the trust from which the income was distributed? The likelihood of the US providing a foreign tax credit in respect of the income attributed to the (US resident) beneficiary could then be limited by this technicality. The beneficiary may need to invoke the MAP to remedy this situation and would need to prove that the tax imposed on income attributed to them results, or would result, in taxation not in accordance with the provisions of the treaty (Article 24(1)(a) of the Tax Treaty. As a US resident, the beneficiary would need to submit their case to the IRS (Article 24(1)(b)). This issues is discussed in detail in our Structuring cross-border transactions: part 2 white paper.

What does the MAP process entail?

The ATO identifies two double taxation situations that allow for the MAP process to be invoked:

- Juridical: Where a taxpayer is subjected to tax on the same income in two jurisdictions. This can arise when the taxpayer is a resident of two jurisdictions or when the taxpayer earns income from another jurisdiction.

- Economic: Where two different taxpayers are subjected to tax on the same income in different jurisdictions. This arises when a taxpayer’s taxable income is adjusted according to the arms-length rule/transfer pricing adjustment.

Double taxation issues must first be attempted to be resolved by applying any foreign source income exemptions or offsets, foreign tax credits, residency tie breaker rules and exclusive taxing rights before the MAP process can be invoked.

A MAP request can be made by a taxpayer to the ATO when there is a probability of being taxed in a manner that is not in accordance with the provisions of the applicable Tax Treaty or if the taxpayer has, in good faith, initiated an adjustment to their tax return. The request must be submitted to the relevant authorities and must contain all information relevant to the case including, any supporting documentation along with information regarding MAP requests to other taxing authorities. The ATO limits the timeframe for the MAP request to be within three years of a taxpayer having knowledge of the likelihood of the tax discrepancy.

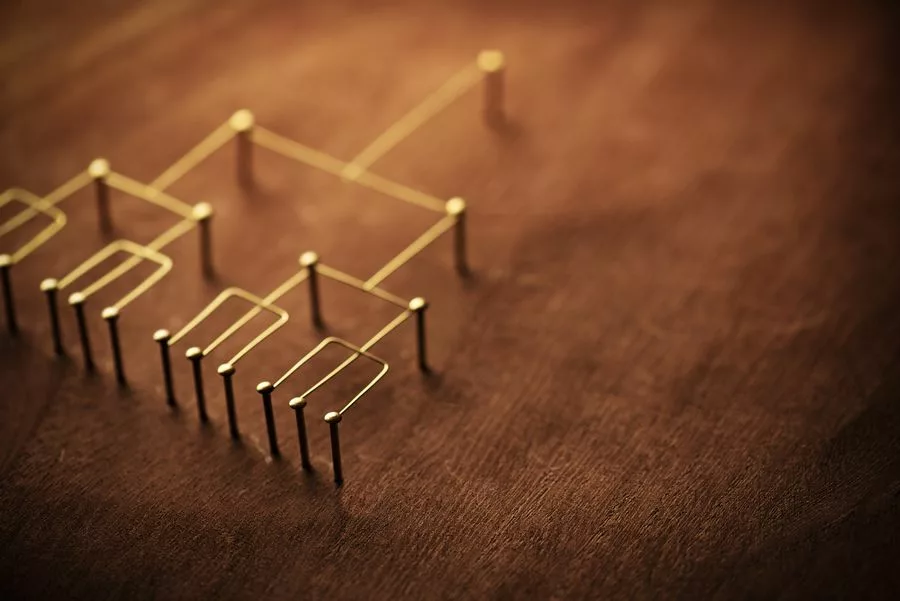

Stages of a MAP case (Article 24(1) of the US-Australia Tax Treaty):

- the taxpayer submits their case to the relevant Competent Authority;

- the Competent Authority determines whether the case is justified and whether a unilateral solution can be imposed; and

- if a unilateral solution is not possible, negotiations take place between the relevant Competent Authorities during which they attempt to reach a mutual agreement for the resolution of the case.

While independent and binding arbitration for issues that remain unresolved after two years under the MAP is provided for in some Australian tax treaties, (or will be provided for by modification by Part VI of the OECD Multilateral Convention to Implement Tax Treaty Related Measures to Prevent Base Erosion and Profit Shifting), this is not yet the case with the US-Australia Tax Treaty. So, for some taxpayers, these issues may go unresolved.

For more information please contact:

Renuka Somers- Head, US-Australia Tax Desk

Zara Arsiwalla- Associate, US-Australia Tax Desk